Excerpts From My Unpublished Dissertation “losing Chandler: Homoerotic Torsions and Tensions in the Early 21st Century”

So, this is the new normal. Under lockdown, we wear our masks, wash our hands, and scroll the days away while waiting for Miss Rona to see herself out. But there’s no need to be lonely while alone: DADDY is putting the social in social distancing for our QUARANTINE issue.

There’s probably nothing to be done with my exhaustive and pointless knowledge of Friends, a fairly average sitcom from the 90s. But imagine if there was.

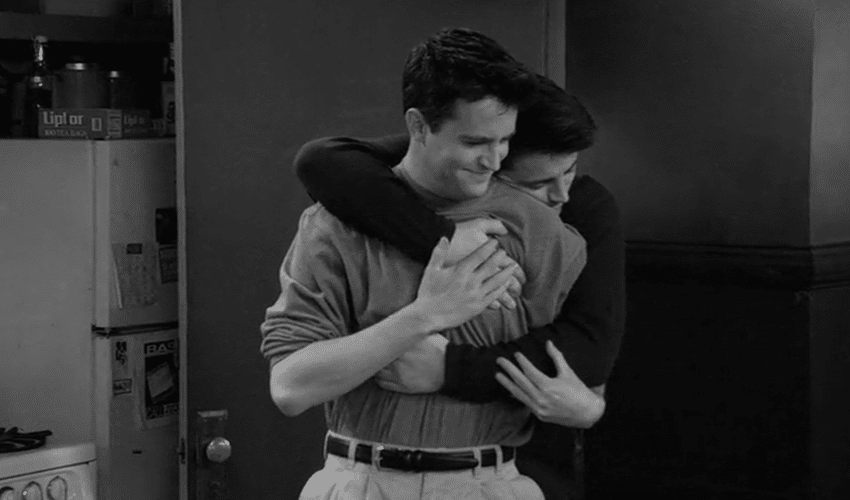

Chandler Bing’s early childhood trauma from a series of dysfunctional parenting tactics—announcing a divorce over Thanksgiving Dinner, forcing a young boy to participate in a sexualised drag act—is translated into a virulently homophobic adult personality, one that is unable to either recognise or acknowledge Joey’s bisexuality. And when Joey temporarily moves out of their shared apartment after their relationship fractures (“The One Where Joey Moves Out.” Friends: The Complete Second Season, written by Betsy Borns, directed by Michael Lembeck, Warner Brothers, 1995), the only expression of affection of which Chandler is capable is accepting a hug, his back turned.

If we take “hand” here to read as a broad signifier of the body, or perhaps of bodily agency, as implicit in the hand’s ability to take and touch, or more potently of bodily desire, Joey’s discovery of his “identical hand twin” in “The One In Vegas (Part One)” implies a deeper logic operating under the latest of Joey’s madcap or ‘brainless’ schemes. “It’s a guy with my identical hands,” he explains, with all the joy and infatuation of a teenage crush. “It was incredible! Chandler, the dealer’s hands were exactly like mine! It – it was like looking at my hands in a mirror!”

What Joey is searching for, hidden under the unusually broad lighting of the Vegas casino, is perhaps not so much a hand twin as a bodily agency twin: a man who will reciprocate his desire, a man who possesses the same homoerotic urges as Joey.

But the oppressively heterosexual world that Joey works within will not allow it: he is ridiculed by Chandler, and feared by his “identical hand twin”; a man perhaps more canny about the homophobic environment they are moving within. Joey’s sweet, fervent sense that “you and I have been given a gift. Okay? We have to do something with it… We could clap our hands together, people will love it!” is met with anxiety and confusion by his identical hand twin. “Stop it,” the unnamed man says, with a low, fevered energy. “Please stop it.”

This sense Joey has of hands holding and clapping, of male hands becoming indistinguishably intertwined and exchanged (“This hand is your hand, this hand is my hand, oh wait, that’s your hand; no, wait, that’s my hand!” is the theme song of his imagined future) is once again unreciprocated; is met, in fact, with Foucauldian violence and enforcement, as Joey is dragged out by a security guard.

Tangentially and tragically, Chandler attempts to come to terms with this desire, couching it in the same language of success and money (“a million-dollar idea”) that Joey has, himself, disguised it with. “I support you one hundred percent,” Chandler tells him, clearly lying. “I just didn’t… get it right away.”

But Joey has been waiting for Chandler to “get it” for a long, long time.

In Joey’s patient desire to nap with Ross, we see again the loneliness of the closeted ‘ladies man’ surfacing. “[Napping on the couch is] where I’ll be,” he says, with a meaningful look, and is followed by Ross upstairs to engage in a forbidden gentle intimacy that prizes same-sex love, closeness and safety. Ross’s approach to gender may blur as the seasons progress. ”I’d prefer not to answer that right now,” he tells Joey fussily when Joey asks how much he weighs, “I’m still carrying a little holiday weight,” (“The One Where They’re Up All Night.” Friends: The Complete Seventh Season, written by Zack Rosenblatt, directed by Kevin S. Bright, Warner Brothers, 2001); later in the season, he, Chandler, and Joey will engage in a cheerful homosocial ritual of applying face masks (“The One With The Cheap Wedding Dresses”), unburdened by heteronormative standards of cleanliness. However, he ultimately remains an aggressive moderator and enforcer of toxic masculinity within the universe of the show: firing the male nanny he cannot stand, refusing to allow his son to play with a Barbie. Sedgwick provides a clear framework for the world that Ross operates in, outlining how the development of a “crystallized male homosexual role and male homosexual culture” was crucial in the creation of “a much sharper-eyed and acutely psychologized secular homophobia… The historically shifting, and precisely the arbitrary and self-contradictory, nature of the way homosexuality (along with its predecessor terms) has been defined in relation to the rest of the male homosocial spectrum has been an exceedingly potent and embattled locus of power of the entire range of male bonds…

Because the paths of male entitlement, especially in the nineteenth century, required certain intense male bonds that were not readily distinguishable from the most reprobated bonds, an endemic and ineradicable state of what I am calling male homosexual panic became the normal condition of male heterosexual entitlement.” (Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Epistemology of the Closet, University of California Press: 1990, p.185) It is Chandler, undoubtedly, who operates at the most distressed level within this realm of male homosexual panic. But it is Ross, ever-vigilant, who patrols it.

Crane and Kauffman’s stranded creations close, to the gentle background of the laugh track, a series of doors in Joey’s face, a brutal hegemonic shut-down of Joey’s attempts to cross boundaries and subvert binaries. At first encouraged by eclectic sadomasochist Phoebe to try on women’s underwear, he is quickly subdued for enjoying it too much. “I think it’s important that you do [take them off],” Phoebe says, highlighting the implicit violence of the group’s rigid identity systems.

Who will be where for whom?

Get DADDY in your Inbox

Stay in the loop by subscribing to our newsletter